How Culinary Education Parallels Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

01 October 2019Culinary curriculum sequencing should mirror the progressive, sequential needs from survival to actualization described by Maslow’s theory.

By Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC

One point is very clear when it comes to building an effective culinary program: the learning process of trade skills must be progressive. Unlike many other college majors where much of the content can be in independent silos with few prerequisites – culinary arts must be built methodically knowing each skill prepares a person to understand the next skill.

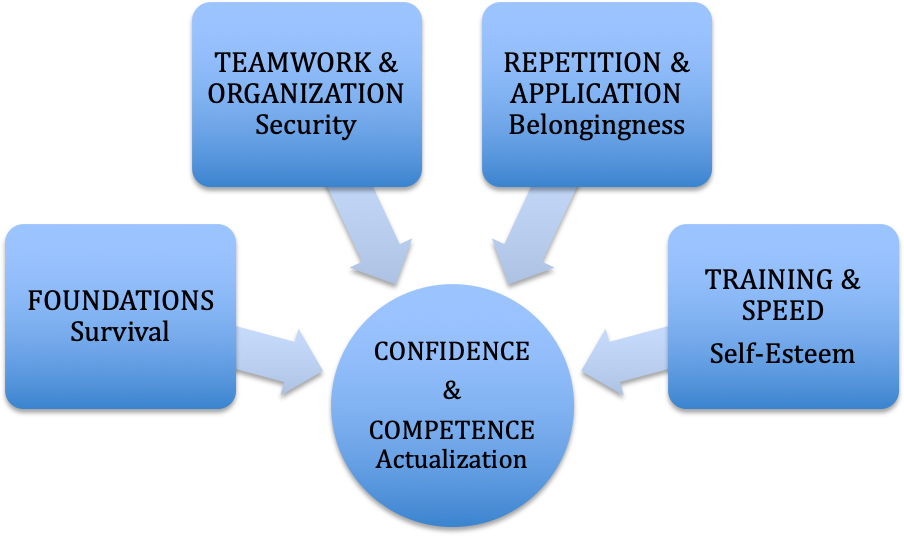

It is also clear that these progressive skills build from a strong foundation. Each learning step along the way connects to a level of confidence while addressing critical human self-motivational needs defined by Abraham Maslow.

The best programs are ones that are focused on building a learning organization – one where true learning is at the core of everything the program seeks to accomplish. This learning involves not just the student, but equally important – the faculty, staff, advisors, and even those chefs and restaurateurs who hire a programs’ graduates. Great results happen when this connectivity loop is complete.

Abraham Maslow stated that self-motivation happens when sequential needs are met. This begins with a survival foundation – individuals must be able to count on those factors that allow them to meet basic needs. In the culinary arts kitchen this could be those foundational skills like knife handling, sanitation, understanding basic cooking methods, and the basic nutrition principles. Until those needs (skills) are met it will be difficult for a student to progress through the process of learning how to cook. In this instance – teaching, rather than training, is critical. There needs to be ample opportunity for paced, individual attention, a forum for asking questions, observation through demonstrations that establish performance benchmarks, and time for outside assignments and research. Understanding is the key in this learning phase as practice and competence will follow.

Next, it becomes essential for individuals to feel secure with their environment. This takes place in a team environment – working with others, depending on the person beside you, and the presence of an organized workspace that is comforting and appropriate for the work to be done. Teamwork is the rule during this phase as students discover how to depend on others, accept roles in a production environment, and communicate and share. Although some production is critical in this part of a program – teaching is still the key to cook development.

The third phase involves repetition and application in an environment that is live and real. In this phase, the student will feel the positive impact of belongingness. Faculty members begin to transition from the “sage on the stage” to the “guide on the side.” Progressive learning happens as students build work habits, solid work ethic, functionality within a system, and start the learning process on how to solve problems through their missteps and failures. Working through this battle phase leads to a significant jump in confidence.

The fourth step happens when the student moves from a somewhat sheltered teaching environment to one that is exclusively training focused. During this phase, the student is driven to build speed, accuracy under pressure, consistency, dependability, and assimilate from their surroundings. This is a cooking and operational management style and philosophy that will carry them through their career. This leads to a high level of self-esteem. In most cases, this happens on an internship or externship experience. It is critical the college build strong relationships with the internship sites that understand their important role and represent the very best operational procedures that define our industry. This is the time when students truly transition into a competent cook.

When all phases are in sync, the student then becomes competent and confident. Confidence leads to better performance and trust and directs the student to self-actualize. This is the kind of worker in demand today.

So, if you break a culinary learning organization into visual components that parallel Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs it would look like this:

Whether the goal is to train a cook for full-service, fine dining, business and industry production environments, product development, or chain restaurant management – these steps or phases are essential. Program leadership would be wise to keep this sequence in mind as they develop curriculum. If the program is to strive to become a true learning organization then this progression would be appropriate for all those involved in the planning, execution, and receipt of educational content.

PLAN BETTER – TRAIN HARDER

Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC, president of Harvest America Ventures, a mobile restaurant incubator based in Saranac Lake, N.Y., is the former vice president of New England Culinary Institute and a former dean at Paul Smith’s College. Contact him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..