Change Your Approach to Kitchen Fundamentals

06 August 2024Re-thinking curriculum and making confidence the end game.

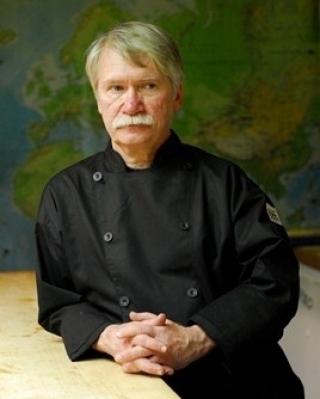

By Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC

Feedback & comments: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The more I reflect on my time as a chef, manager, teacher, and program administrator, the more I am convinced we (in all the above positions) have for a long time been approaching our craft incorrectly. When we stop for a few minutes, look around at other skill-based professions and apply what we see to our situation, the more I feel you will come to the same conclusion.

I watched videos of coaches working drills with young basketball, baseball, hockey and football players. Their approach was the same: work on a focused skill repeatedly until it is right. Then, work on it some more. Interject a variable (challenge) and see how the athletes react. Repeat the variable time and again, until they UNDERSTAND how to prepare for it and ACT rather than react. Talk about the drills afterward, watch films or games where others face similar challenges and plan how they would ACT if faced with the same challenge. Scrimmage with excellent players and do so often enough that they can imitate their actions.

I saw how technique is practiced time and again until everything becomes second nature. Athletes learned how to hold the stick, the mechanics of throwing a ball, the technique of swinging a bat, the right way to push a basketball toward the hoop to gain the greatest power, how to stop and go while at a full run, the right way to bend knees, twist their body, or fall without injury.

The result is strength, skill, competence, confidence, understanding and success. Practice is more important than the game. It is the practice that develops excellence, and it is the expectation of excellence that makes every player understand this must be how they approach everything.

What are we trying to accomplish in our kitchens and classrooms? We are expected to train successful cooks who eventually may become chefs and facilitate the production of delicious, beautiful food. Are we successfully accomplishing these goals? The more I study this question, the more I am convinced the answer is no – at least not consistently and at the level that we could and should.

Our vehicle for accomplishing these goals is the curriculum that directs us and the methods we use to deliver the material. Based on what I have seen and experienced, I propose a shift toward KEEPING IT SIMPLE AND DOING IT EXTREMELY WELL.

We should seek to reach competence as it leads to confidence. Confidence reduces stress, improves focus, increases learning speed, helps with time management, and maintains a focus on something attainable. Competency-based education is the best approach toward deeper learning.

Competency-based approach components

Practice

Repetition

Analysis

Critique

Technique

Imitation

Challenge

Excellence

Athletes who spend an hour a day, every day, practicing dribbling a basketball will build ball-handling skills that are as important, if not more, than shooting at the basket. It may seem boring to some, but eventually the mechanics of dribbling become second nature and the hands and fingers UNDERSTAND where the ball is, where it will be, and how to weave through a line of defenders. The same is true with the mechanics of throwing a football or controlling a hockey puck.

One could safely assume that the same is true with knife skills, managing a busy station on a restaurant line, learning degrees of doneness for a steak, or understanding the “feel” of a sourdough before being shaped into a loaf of bread. The more you do it, the better you become. The better you become, the greater your level of competence. The higher your level of competence, the greater your level of confidence.

When any coach is asked to assess where their team sits at half-time in a game, they almost always say the players should work harder at the fundamentals: blocking, tackling, catching, passing, ball control, attacking the net, or skating dexterity, etc. In other words, the players must remember the foundational skills they have practiced over and over. This is how games are won.

Let’s look at our curriculum from this perspective and focus on the fundamentals and how we approach them. Our students will never learn how to bake great bread unless we do the following:

- Show them what great bread looks and tastes like

- Give them a chance to observe how great bread is put together and then allow them to imitate such

- Have them make countless numbers of loaves and analyze each loaf until they reach the excellence level that is their benchmark

- Never accept anything short of excellence (there are no “C” loaves allowed)

- Guide them through the full understanding process so that technique is second nature

- Challenge them to problem-solve by throwing them a curve ball (change oven temperature, over-proof the loaf, use the wrong flour, forget the salt, kill the sourdough starter, etc.)

- Never let mediocrity slip into the daily routine

Do the same with every other foundational skill you know is critical to success. Push aside those things that are NICE or TRENDY and stay focused on the fundamentals. This is how great cooks are made and excellent chefs are born.

Isn’t it time for us to challenge what, why, and how we have approached our positions in favor of the desired outcomes that have always been there?

PLAN BETTER – TRAIN HARDER

Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC, president of Harvest America Ventures, a mobile restaurant incubator based in Saranac Lake, N.Y., is the former vice president of New England Culinary Institute and a former dean at Paul Smith’s College. Contact him atThis email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..