Lifelong Learning is Like Riding a Bike

05 November 2024Discovering the desire for excellence drives the need to learn and improve.

By Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC

Feedback & comments: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

I watched my grandson work to learn to ride a bike over the past few months. I remembered doing so myself with my father holding onto the back of the seat, pushing me to build speed and encouraging me to take the risk of balance and coordination. There were days when I wanted to give up, lock the bike in the garage and move on to something else. There were moments when I fell and wound up with scrapes and bruises but, somehow, I kept going until…ah, the freedom of transportation.

While I watched my grandson finally take off, peddling away, finding his groove and smiling from ear to ear I gave thought to the larger picture. What he learned at this moment was how he could apply this same method to everything that lies ahead. Commitment, patience, investment, the “I can” attitude and a willingness to learn – these attributes will open many doors for him throughout life, just as it did for me. Learning to ride a bike was the beginning.

The mind is an incredible organ; its capacity is yet to be fully understood but its potential is seemingly limitless. There is no age limit to learning and understanding; the only limitation is our willingness to seek it.

As educators, we are in the business of relaying information and nurturing skills development. This is our training but is this enough? Peter Drucker, one of the great management gurus of the 20th century, once wrote:

“We now accept the fact that learning is a lifelong process of keeping abreast of change. And the most pressing task is to teach people how to learn.”

Let’s for a moment think about that. We know the skills we have today – whether culinary skills, management and/or leadership skills, are fragile. Sure, everything we learned is important and everything we teach in classrooms and kitchens is and will remain important. But do we know these skills have a shelf life? The way our mentors taught may not work today. Culinary skills, the way people eat, and the equipment we use – all of this has changed and will continue to change. We must view what we do and teach our students so that it remains fluid.

If Peter Drucker is right, then maybe, just maybe, our job description should be adjusted.

Everyone needs to learn how to learn and update their base of knowledge. Everyone should remember how enjoyable it is to continuously learn. Maybe, instead of relaying information and developing skills, our responsibility is to show people how to learn and set an example by doing so ourselves. Arie de Geus, a business theorist, said:

“The ability to learn faster than your competitors may be the only sustainable competitive advantage.”

Our ability as educators to strive for excellence and our students’ ability to make a dent in the universe, may very well be determined by:

“…pushing yourself to acquire radically different capabilities—while still performing your job. That requires a willingness to experiment and become a novice again and again: an extremely discomforting notion for most of us.”

Harvard Business Review, Learning to Learn – Erika Andersen, March 2016

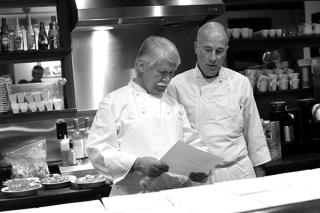

This sounds great, but how do we teach students how to learn? Well, let it begin with you setting the example. How committed are YOU to constantly seeking a higher level of understanding, a greater breadth of knowledge, and new physical skill sets? Is this part of your everyday approach to not just your job but the life you live? Is your enthusiasm for learning well known by all? When was the last time you enrolled in a course, spent time as a stagiaire at a great restaurant, attended a conference or workshop, or simply sat down and read a book that helped you think differently? If you have, did you share what you learned with others?

The elements of learning:

The desire to learn

Create an environment of curiosity where students and peer instructors want to discover the why and how. Inspiring students with benchmark examples, engaging them with dynamic people enthused with discovery, and engaging them with stories demonstrating possibilities will help set the stage for a desire to learn.

Knowing what they don’t know

The NEED to learn is driven by the realization that a person doesn’t have the depth of knowledge, or the skill set to complete a task or aspire to a position. Presenting examples of work that is beyond their capability while also showing how they can “get there” is a way to light a fire and encourage learning to take place.

A culture of excellence

A culture of excellence becomes an environment of excellence with everything you do in the classroom and kitchen exudes excellence, when you expect nothing less from your students and when you demonstrate excellence at every turn outside the classroom.

When excellence is expected, recognized and rewarded, then excellence is what all will strive to achieve. The desire for excellence drives the need to constantly learn and improve. It is what the Japanese refer to as “Kaizen” – or a belief in continuous improvement.

PLAN BETTER – TRAIN HARDER

Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC, president of Harvest America Ventures, a mobile restaurant incubator based in Saranac Lake, N.Y., is the former vice president of New England Culinary Institute and a former dean at Paul Smith’s College. Contact him atThis email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..