Think Tank: Intensity, Realistic Environments and Tempering through Experience

10 January 2014

Does your program meet the needs of the industry it serves and adequately prepare your students to shine?

Does your program meet the needs of the industry it serves and adequately prepare your students to shine?

By Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC

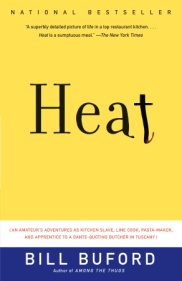

I just finished re-reading Bill Buford’s book, Heat: An Amateur's Adventures as Kitchen Slave, Line Cook, Pasta-Maker, and Apprentice to a Dante-Quoting Butcher in Tuscany,about his hands-on experiences on the line in Mario Batali’s restaurant and subsequent time working with arguably the finest butcher in all of Italy.

As I finished this great depiction of the learning process in kitchens I was again inspired to look at how we prepare students for the rigors of the kitchen. What came through very clearly in Buford’s story (and from my own experiences as a chef) was the intensity of the kitchen and the realization that a strong culinary program must be able to recreate this intensity if students are truly destined to “learn.”

There is a difference between teaching and training, and both must be present in a curriculum if the end result is a graduate who is “kitchen ready” today and “career ready” tomorrow. What operational chefs are looking for in culinary graduates is a strong foundational knowledge of cooking, positive attitude, willingness to learn, the ability to work with others as a team, efficiency, stamina and the ability to multi-task under pressure.

To me, it only makes sense that this should be the starting point in building a modern culinary curriculum. Every course built, every lesson plan designed, every facility built and every faculty training session should reflect back on these expectations. Does this design meet the needs of the industry it serves and adequately prepare our students to shine?

There are numerous ways that a program can be built around this intensity, ways that can take place in the classroom and in the kitchen. Faculty members can build every assignment around short deadlines that require students to problem solve and stay on task. Projects can be introduced that force students to work collaboratively and instill the best use of time, space and team dynamics. Scenario planning can and should be part of every situation that students are placed in. “What if” should always be a component designed into student work. It will be those “what if” solutions that will allow students to thrive when they are in a kitchen.

Kitchen laboratory classes need to be designed to emulate realistic environments and cooking lessons should always include tight deadlines, the need for collaboration, assessment of organization, grace under fire and speed. At the end of each lab students could be evaluated based on those expectations of the chefs they will eventually work for. We need to “teach” students about food, process and the ways to set the stage for that future position as a sous chef. We need to “train” students how to be effective, focused, competent cooks who can meet the demands of a busy kitchen. This is the portal to those future management positions and cannot be underplayed.

In the end, it will be the addition of well-organized and supervised internships and externships that will bring everything together. Have you viewed your curriculum, facilities and staff in relation to these parameters? If not, it may be time to do so. Those programs with a reputation for building “kitchen ready” graduates are the ones that will attract the best entering students, the most supportive internships, the most enthusiastic recruiters, and the industry support that will allow them to thrive in a highly competitive education market.

Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC, president of Harvest America Ventures, a “mobile restaurant incubator” based in Saranac Lake, N.Y., is the former vice president of New England Culinary Institute and a former dean at Paul Smith’s College. Contact him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., www.harvestamericaventures.com.