The Cyclical Nature of Turkey Farming

31 October 2018Thanksgiving day turkeys grown from poult with care, love and experience in northern Minnesota.

By Lisa Parrish, GMC Editor

Feedback & comments: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

November with its cooler days and diminishing sunlight signals for many a change. That difference could be the beginning of the holiday season or the end of the growing season. For Minnesota turkey farmer John Burkel, it means his turkey houses are quiet, the cleaning process has begun, and more family time becomes available. It’s also the time of year when nearly every turkey he’s grown is consumed – Thanksgiving. Well, except for one presidential turkey five years ago.

November with its cooler days and diminishing sunlight signals for many a change. That difference could be the beginning of the holiday season or the end of the growing season. For Minnesota turkey farmer John Burkel, it means his turkey houses are quiet, the cleaning process has begun, and more family time becomes available. It’s also the time of year when nearly every turkey he’s grown is consumed – Thanksgiving. Well, except for one presidential turkey five years ago.

Burkel’s Badger, Minn., farm grows whole turkeys primarily for Thanksgiving. In 90,000 square feet of barn space spread between four grow houses, he can produce between 1 and 1.5 million pounds of turkey from approximately 80,000 hens yearly.

In turkey farming, as it is with almost all industries, demand drives production.

According to Burkel, gone are the days when most households want a 20- to 25-pound bird to celebrate the holiday. “Consumers want smaller portions these days,” he said. “Our production is sales driven. We grow our hens to around 14 or 15 pounds because that’s what people want.” On Burkel’s farm, that takes about 13 weeks and he grows nearly all hens as they are smaller birds. Toms (male turkeys) are larger and usually grown for deli meats, wings, or turkey breast.

The hens on Burkel’s farm, which is about 15 miles from the Canadian border, mainly eat canola meal with added vitamins and minerals. He says his feed includes more wheat than corn because of what is available locally. The turkey’s meat texture and taste can be affected by feed. “The fat will be whiter and there can be a difference in texture in a bird that has more corn in its feed,” he said.

This past year the fourth-generation farmer began a new venture - growing organic turkeys. “It went well and was a great learning experience,” he commented. He said it’s similar to growing hens in grow houses, except the birds are fully maintained outside and there are more restrictions on feed and antibiotics. Even though he was raising the hens organically, his main concern remained the birds’ health. “If I hear a cough or they look a little piqued, I am going to do something. We never put the health of the flock on the back shelf.” With the organic hens that might mean giving them an essential oregano oil, which has antibiotic properties, or judiciously applying an FDA-approved antibiotic to his hens in the grow houses. “Every day that it’s not a good day for the hens (then) it’s not a good day for me. We have to balance animal welfare with the antibiotic-free process. We just want to do the best thing for the bird.”

Burkel is part of a farming production co-op, Northern Pride, that includes about 25 growers. Between all the farms, they produce nearly 40 million pounds of turkey each year. Four growers chose to grow organic flocks this year with four or five additional set to undertake the process in February 2019 when the growing season begins again.

Burkel didn’t start out wanting to follow in his father’s turkey growing footsteps. He began college majoring in economics and thoroughly enjoyed it. However, as time progressed, he couldn’t see himself in the city. “Looking back on it, it (farming) was an easy opportunity to fall back on. The opportunity to have my own business, manage my time and have my kids on a farm was too great,” he said. Flash forward more than 20 years, he now has five children and continues to grow turkeys just down the street from his dad’s farm.

Burkel didn’t start out wanting to follow in his father’s turkey growing footsteps. He began college majoring in economics and thoroughly enjoyed it. However, as time progressed, he couldn’t see himself in the city. “Looking back on it, it (farming) was an easy opportunity to fall back on. The opportunity to have my own business, manage my time and have my kids on a farm was too great,” he said. Flash forward more than 20 years, he now has five children and continues to grow turkeys just down the street from his dad’s farm.

“I like the seasonality of growing turkeys,” he said. At the end of the calendar year near the holidays, time is spent cleaning the barns and spending time with the family. “By January I’m done with the holidays and everything is buttoned up and we are hunkered down,” he said. But, February arrives and the barns are warmed in anticipation of accepting the new turkey poults, day-old birds, and the growing season begins again. By March or April, orders for the following Thanksgiving are between 70 and 80 percent finalized. “We are in the business of under promising and over producing,” said Burkel.

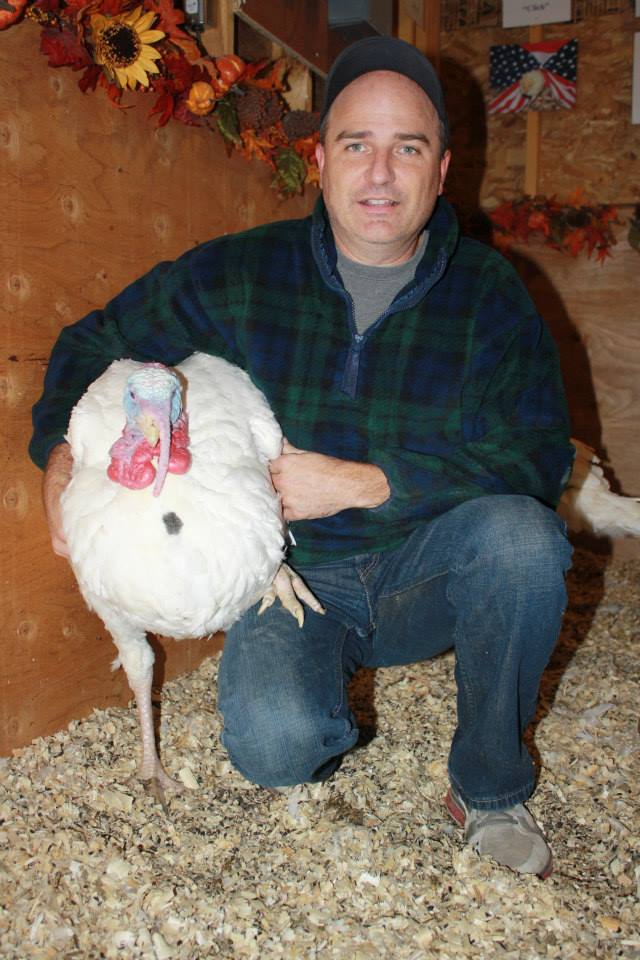

In 2013, Burkel, who at the time was Chairman of the National Turkey Federation, did raise a flock of toms. However, it was in preparation for growing the turkey that then President Barack Obama would pardon at Thanksgiving. “That was really fun,” he commented. The new flock began with 80 toms in July. After five weeks, Burkel pulled out 20 turkeys to evaluate for the pardoning honor. He built a shed in his backyard so he could watch the birds and interact with them. Out of those, he choose two birds. “I wanted them to get used to human interaction. Really, I hoped president didn’t get a wing to the head,” he laughed. As it was, the president and his daughters pardoned Popcorn, the final bird selected for the ceremony, without any mishaps.

In 2013, Burkel, who at the time was Chairman of the National Turkey Federation, did raise a flock of toms. However, it was in preparation for growing the turkey that then President Barack Obama would pardon at Thanksgiving. “That was really fun,” he commented. The new flock began with 80 toms in July. After five weeks, Burkel pulled out 20 turkeys to evaluate for the pardoning honor. He built a shed in his backyard so he could watch the birds and interact with them. Out of those, he choose two birds. “I wanted them to get used to human interaction. Really, I hoped president didn’t get a wing to the head,” he laughed. As it was, the president and his daughters pardoned Popcorn, the final bird selected for the ceremony, without any mishaps.

As for what’s on Burkel’s Thanksgiving table, he laughed and said turkey. Then he remembered a story from early in his marriage. “We were going to my in-laws for Thanksgiving and they served prime rib. It didn’t over well.”