Recovering Food Waste: How an Action Plan Came to Fruition

05 November 2024CIA’s Robert Perillo shares his journey planning and implementing a food waste recovery program that donated over 121,000 pounds of food since its inception.

By Robert Perillo, CHE, Culinary Institute of America at Hyde Park instructor

Feedback & comments: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Beginning a food waste recovery program took a great deal of commitment, perseverance through setbacks, a little luck and an instructor who would not give up. Read how Robert Perillo built a food recovery program that positively affects the Culinary Institute of America at Hyde Park’s triple bottom line – the people, planet and bottom line.

Beginning a food waste recovery program took a great deal of commitment, perseverance through setbacks, a little luck and an instructor who would not give up. Read how Robert Perillo built a food recovery program that positively affects the Culinary Institute of America at Hyde Park’s triple bottom line – the people, planet and bottom line.

(Editor’s Note: Read, “Educating rising culinarians about food donation:Educating rising culinarians about food donation: A comprehensive lesson plan focusing on discussing and comprehending food waste and how it can be curbed through donation” for more information on teaching food waste recovery.)

A journey to recover wasted food

My ethnic upbringing conditioned me not to waste food. This training has been an asset, especially in the restaurant industry where food and labor costs keep you up at night. Reducing food waste is also helpful in controlling domestic expenses and assists during lean times. Reducing (or eliminating) food waste has significant social, economic, and environmental benefits. Culinary education by its nature can be a generator of food waste, not just scraps but edible, servable, nutritious food. How can we address food waste in culinary educational models from theoretical and practical perspectives?

As a culinary arts instructor at the Culinary Institute of America (CIA), I was part of the problem and not the solution. Even though I planned my food ordering and worked to mitigate waste there was overage at times with no outlets. I initiated conversations with administrators and there seemed to be an appetite for developing food recovery systems, but perceived barriers and logistical issues prevented initiatives from moving forward. Some of those concerns were food safety, fear of potential lawsuits, how to collect recovered food, where to send it, how to transport it, and any increased labor costs associated with donating food.

During 2015, I researched and met with numerous stakeholders. By luck, I connected with a Food Sourcing Agent at the Food Bank of the Hudson Valley. We organized a food insecurity event with a partnering Food Pantry/Thrift shop named People’s Place in Kingston New York. There was a Community Outreach Committee comprised of staff members on the CIA’s Hyde Park campus. They were interested in getting involved in the event and recovering food so as a sole faculty member I inserted myself into the Committee.

In the Fall of 2015, the food insecurity event at People’s Place went extremely well. It was a chefs’ challenge, students and staff participated as well as local restaurants. This past summer we celebrated the 10th annual Chefs’ Challenge at People’s Place. People’s Place has become a vital partner that makes available opportunities for the CIA throughout the year to engage with the local community and provide valuable learning experiences for our students and faculty.

Our relationship with the Food Bank of the Hudson Valley began to grow through the initial event. Although the Food Bank deals with bulk items and not with small-scale prepared foods, they were interested in working with us. The Food Bank’s pickup route passed by the campus three days a week.

After months of meetings and planning, the Community Outreach Committee suddenly dropped the initiative and told the Food Bank we were not interested in recovering food without notifying me. I quickly contacted the Food Bank representatives and explained that we would find a way forward.

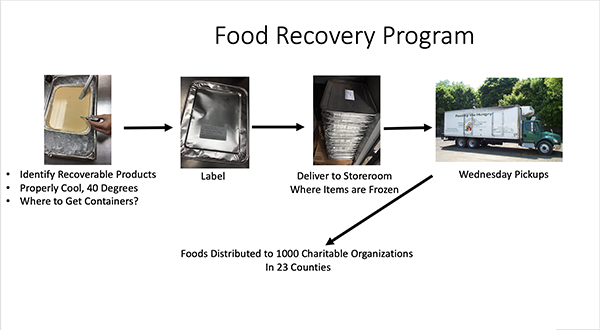

Two vital members of the Community Outreach Committee were also still committed to recovering and donating food. They both worked in the Storeroom, which was the key operational component of the system design. The concept was for chefs and students to identify food products for donation in the kitchen labs. Then place the food in aluminum hotel pans provided by the Food Bank, cool the food, cover, date, and label the containers with stickers, also provided by the Food Bank. The food was then delivered in the containers to the Storeroom. The stickers have specific barcodes for tracking purposes. The Storeroom would aggregate the containers and place them in Food Bank boxes. The Food Bank would pick up the boxes from the Storeroom three days a week. It sounds easy, right?

My goal was to present a written proposal to the President’s Cabinet for approval. Before doing so, I had to confirm and discuss the plan with the stakeholders. First, I went to the Storeroom Manager for his approval. He supported the idea as long as it did not disrupt or strain operations. One problem was how to distribute the containers and labels. After some conversations, we thought our Central Issue warehouse could take that on. Central Issue handles linens, uniforms, and cleaning supplies. The Central Issue Manager was happy to help. Previously, I had met with the Student Government Association (SGA) numerous times for their input. The SGA was very supportive of the idea. I asked the SGA to generate a survey on the topic, which they did. The survey had a large sample of the student body with an overwhelming endorsement for developing a Food Recovery program. I asked the Provost and Culinary and Baking and Pastry Deans for their blessings before advancing a working system. Finally, I went to some chef instructors and asked if they would pilot such a program. Initially, we would just recover soups from our entry-level kitchen lab courses. This activity would add another layer of kitchen management for chef instructors but is also a valuable teaching tool.

I happened to be at a meeting held by the city of Poughkeepsie to plan a food insecurity event while developing the proposal. A member of the New York State Department of Environmental Protection was also attending. During the meeting, I learned that New York State was passing legislation called the Food Donation and Food Scrap Recovery Law. Essentially, the law says that large feeding institutions are required to donate and compost food scraps. This was an important fact to raise as part of my argument; staying ahead of the regulatory curve is always a good thing. Another significant law, central to the enterprise was the Good Samaritan Act, voted into law in 1996, which provides liability protection when donating food in good faith.

(Editor’s Note: Click here to read a Gold Medal Classroom story, “The Food Donation Improvement Act: A Guide for Culinary Educators. New act expands liability protections for food donors and encourages food businesses – including schools and non-profit organizations – to donate.”)

The detailed proposal that focused on education, operations, regulations, economic, social, and environmental benefits of recovering food was submitted and approved by the Cabinet. The Provost, with whom I had multiple conversations about the program, agreed to let me run a pilot. I drafted Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and worked with two kitchen labs to launch the pilot. In the Fall of 2016, we donated our first case of recovered soup. From there, I expanded the program by word of mouth, information campaigns, student engagement, events, and conversations. Since that starting point to the end of 2023, we have recovered over 121,000 pounds of food. There were certainly challenges along the way that we continue to address as the program grows.

Click here to watch a video outlining the food recovery program.

The objective of the program is to educate our students about food insecurity, activism, food waste, and best practices. While addressing our core competencies, we can also make a social impact and shrink our carbon footprint. A major positive externality is the community relations and partnerships that have flourished through our activities. The results have led to internships, externships, events, research, jobs, and important educational opportunities for our students. Collecting prepared foods for donation can result in awareness of overproducing and encourage reduction acts. The food recovery program has yielded numerous positive outcomes all of which benefit the Triple Bottom Line: people, planet, and profits. Reduce, Reuse, Recycle!

Chef Robert Perillo earned the 2024 United Soybean Board Green Award, which recognized his sustainability efforts.