Recovering Food Waste: Overcoming Challenges

05 December 2024CIA instructor Robert Perillo successfully overcame challenges while implementing a food waste recovery program that has donated over 121,000 pounds to date.

By Robert Perillo, CHE, Culinary Institute of America at Hyde Park instructor

Feedback & comments: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

As I wrote in a previous article, I initiated a food recovery program at the Culinary Institute of America’s (CIA) Hyde Park campus. The recovery started slowly in the Fall of 2016 as a pilot program and expanded since. This growth has not come without any growing pains.

As I wrote in a previous article, I initiated a food recovery program at the Culinary Institute of America’s (CIA) Hyde Park campus. The recovery started slowly in the Fall of 2016 as a pilot program and expanded since. This growth has not come without any growing pains.

The biggest issue from the start has been acquiring containers to ship the food in. The Regional Food Bank of the Hudson Valley agreed to supply us with the containers as part of our agreement. Initially, we tried different containers but eventually settled on aluminum hotel pans with lids. These are single-use, so they are not very sustainable or inexpensive, especially since COVID-19. The Food Bank distributes to thousands of participating food pantries and soup kitchens in the region. The organization does not have the resources to recover containers for reuse.

Coordinating the delivery of these containers to the CIA campus proved to be tricky. There were many times when there was no wiggle room in the Food Bank’s budget to purchase containers and lids. We would substitute the containers we used internally and replace them when the Food Bank could deliver. This caused complications with accounting and required additional tracking. Furthermore, the deficits generated flurries of emails, texts, and phone calls, not to mention extra time spent managing the problem. There were also countless occasions when the containers did not end up on the delivery trucks. At times, it was a logistical struggle. Out of guilt, need, and frustration, I searched for grants and funding. After submitting a couple of grants, COVID-19 changed the world, and things ground to a halt, including the grants.

In late 2020, I happened to receive an email by chance from a colleague about a foundation interested in funding sustainability and food insecurity projects. It was a group email, so I answered as quickly as I could. Since then, the foundation has been funding the container and lids. This has helped tremendously from an operational standpoint but, more importantly, lifting the financial burden from the shoulders of the Food Bank. They still supply us with plastic bags for baked goods that don’t need to go into containers.

We have had to work with container quality control. There have been times when we have come across a donation container with two croutons in it or other times there is a plate or ramekin in it. Once or twice, we received bain-maries and stainless-steel hotel pans with hot food covered in aluminum foil.

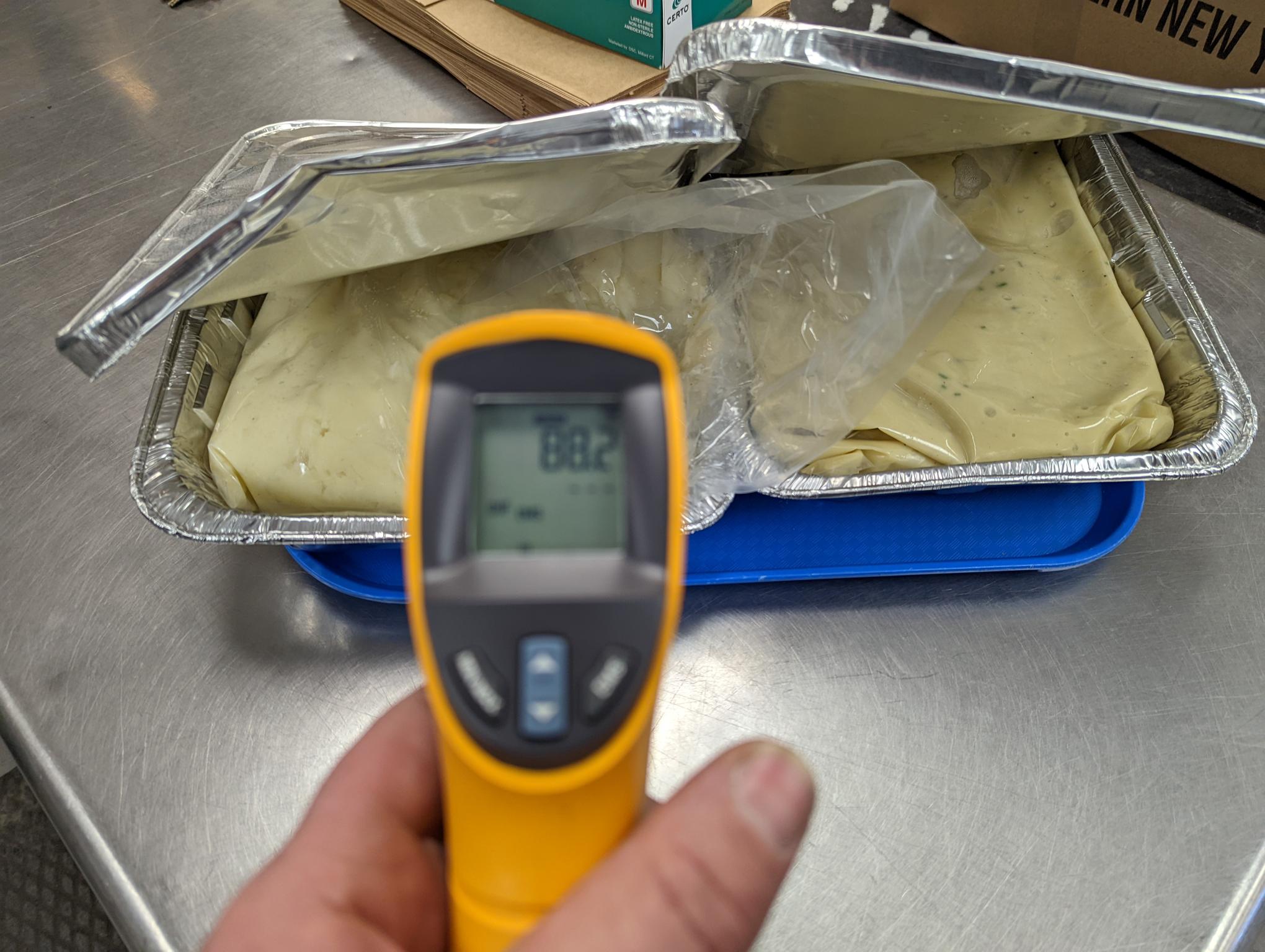

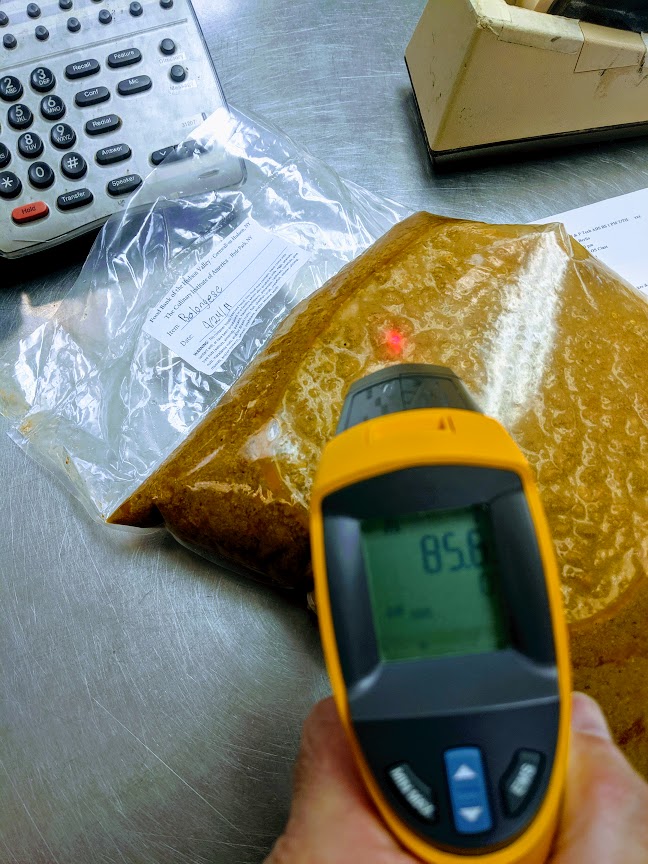

Many CIA teaching kitchens and various events operate each day, so oversight can be difficult at times. Most chef instructors and participants have developed systems for managing food recovery. However, sometimes things get past us. I have developed standard operating procedures that are helpful. Our Storeroom is the hub where all the recovered food gets delivered, and the staff does a great job of monitoring the drop-offs. If a container has not been cooled or labeled properly, they will inform me, and I will address the issue. I have a face-to-face meeting, send out email reminders, do report-outs, and present whenever possible.

The process has smoothed out after eight full years of keeping the system vital. But we still run into minor mishaps. The Food Bank provides us with stickers with a barcode for tracking purposes that provide data for us and the Food Bank. On occasion, the containers are not labeled properly, which is a quick fix on a small scale but can grow into a systemic problem without a timely feedback loop. There are times when the Food Bank cannot pick up, resulting in a backlog on our end. We might forget to tell the Food Bank our schedule around holidays or break times. Before extended downtimes, the Food Bank is happy to absorb any excess perishables. Overall, our collaboration has evolved over the years and is mutually beneficial. Despite setbacks, we have persisted, adjusted, and grown. Overcoming challenges for a common cause has strengthened bonds and expanded the community.

The process has smoothed out after eight full years of keeping the system vital. But we still run into minor mishaps. The Food Bank provides us with stickers with a barcode for tracking purposes that provide data for us and the Food Bank. On occasion, the containers are not labeled properly, which is a quick fix on a small scale but can grow into a systemic problem without a timely feedback loop. There are times when the Food Bank cannot pick up, resulting in a backlog on our end. We might forget to tell the Food Bank our schedule around holidays or break times. Before extended downtimes, the Food Bank is happy to absorb any excess perishables. Overall, our collaboration has evolved over the years and is mutually beneficial. Despite setbacks, we have persisted, adjusted, and grown. Overcoming challenges for a common cause has strengthened bonds and expanded the community.

The food recovery program is not mandatory at the CIA, so the goal is to advocate for participation through education, activism and messaging. Over the last couple of years, students have helped to create Instagram content and videos to inform our campus community of the value associated with food waste reduction.

Conceptually, recovering food in the educational environment is for the sake of education. The intent is to nurture a culture of consciousness, empathy, and activism for generations to come. All the inputs required to produce food are wasted when food is wasted. Food production is heavily dependent on fossil fuels, water, land, topsoil, plastics, packaging, money, human labor, the sacrifices of non-human animals, and the list goes on. When wholesome, edible food goes to waste, the planet and our fellow human animals suffer the consequences. Collecting prepared foods for donation can result in awareness of overproducing and encourage reduction practices.

The food recovery program has yielded numerous positive outcomes, all of which benefit the Triple Bottom Line, people, planet, and profits. Reduce, Reuse, Recycle!

Chef Robert Perillo earned the 2024 United Soybean Board Green Award, which recognized his sustainability efforts.